A recurring theme of failure often emerges in the world of government IT. It’s usually tempting to attribute these failures to the complexities of technology itself. However, the true culprit lies not in the circuits and software, but in something much more fundamental: procurement. The process by which solutions are sought and acquired, even before any digital system is switched on or any software is deployed, plays a pivotal role. This initial step, often overlooked, sets the trajectory for many government IT projects, leading them down a path fraught with inefficiency and ineffectiveness. Understanding this root cause is essential to grasp why so many well-intentioned projects fail to meet their objectives.

Agencies, driven by budget constraints and regulatory mandates, are inclined to select vendors offering the lowest bids. This approach, while financially prudent at first glance, harbors significant pitfalls. The solutions provided by these low-cost vendors frequently meet only the bare minimum of requirements, lacking the flexibility and scalability necessary for evolving governmental needs.

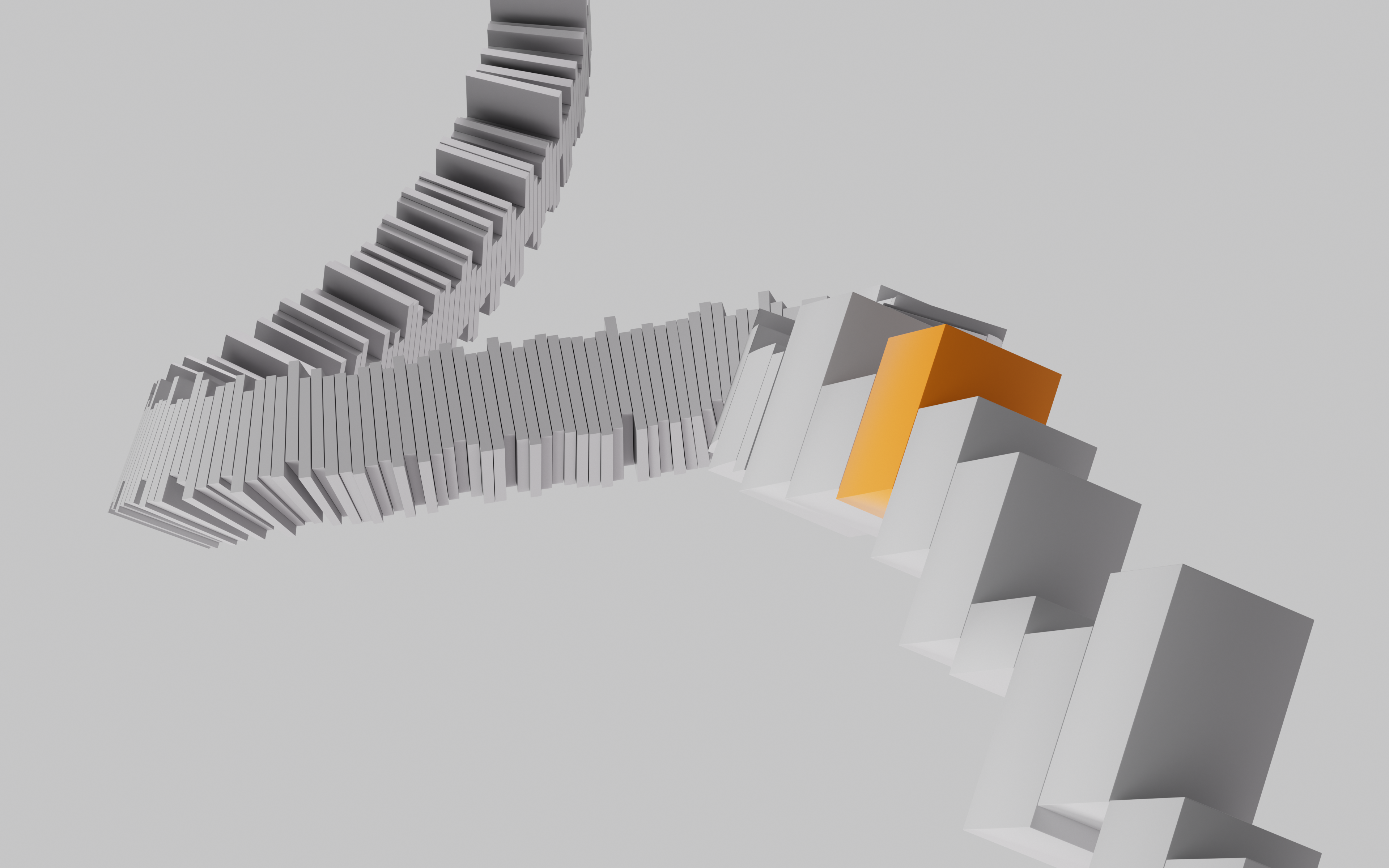

As a consequence, agencies find themselves trapped in a vicious cycle. The rigid and inflexible nature of these inexpensive solutions necessitates a series of costly customizations and change orders. This not only leads to escalated costs in the long term but also hinders the very efficiency and innovation these projects aim to achieve. The irony is palpable—in an attempt to save funds, government entities end up spending more, both in financial terms and in lost opportunities for technological advancement.

After the tragic events of September 11, the Pentagon faced a moment of introspection. The harsh realization that the response to such a modern threat was dependent on fleets of B-52 bombers from the 1950s highlighted a critical issue: outdated and inadequate technological capabilities. A thorough review revealed that this was not merely a failure of technology but a systemic issue rooted in acquisition processes and entrenched bureaucratic hurdles within the Department of Defense. The department’s acquisition procedures were mired in a web of bureaucracy, making it challenging to procure new, more suitable technologies.

1. Consolidate authority

In essence, acquisition authority is scattered across various organizations, and it continues to be scattered. There are numerous veto powers and authorities for checks and balances that reside outside of the mission chain. So, if someone says, “I need an airplane that can do X, Y, Z,” they have to convince a variety of people who have no direct impact on the success of their mission that it’s worth pursuing.

The distance between the contracting officers and the acquisition team tasked with executing the requirement often results in a significant misalignment. This misalignment breeds inefficiencies, as the needs and outcomes desired by the project team are lost in translation across the bureaucratic layers. Consolidating acquisition authority within closer proximity to the project teams can dramatically reduce these frictions and align the procurement process more closely with the project’s intended outcomes.

2. Flexibility in contract vehicles is essential

Right from the start of a project, there is a significant dissonance between what the buyer wants, what they think they want, and how they communicate that to a vendor. When the vendor enters the picture, they are not always incentivized to correct the buyer’s mistakes from the beginning. They are merely responding to a Request for Proposal (RFP).

A shift towards flexibility in contract vehicles, where the focus is on collaborative solution crafting rather than ticking off a requirement checklist, can be transformative. This approach encourages a partnership mindset between government agencies and vendors, fostering innovation and efficiency. It’s about moving beyond the conventional procurement paradigm to one that values strategic, long-term outcomes over short-term fiscal frugality.

3. Develop a willingness to experiment and to fail fast

Embracing an agile philosophy in government IT projects is crucial. This involves acknowledging that not all initiatives will be successful and that failure, when it occurs, can be a valuable learning tool. The traditional reluctance to take risks in government projects often leads to missed opportunities for innovation. Adopting a mindset that encourages experimentation, even if it involves an element of risk, can lead to more dynamic and effective solutions in the long run.

This philosophy necessitates a cultural shift within government entities—a shift towards seeing failure not as a setback but as a stepping stone towards finding the most effective solutions. This can be facilitated by establishing streamlined feedback processes and a willingness to iteratively improve or pivot when necessary. Such an approach not only fosters innovation but also aligns more closely with the rapidly changing technological landscape.

Getting to the root of the problem

The repeated failures of government IT projects are not predestined, nor are they primarily failures of technology; they are, more often than not, failures of procurement. The journey from initial vendor selection to project completion is fraught with challenges, many of which stem from outdated, cost-centric procurement practices. This analysis, drawing from real-world examples like the Pentagon’s post-9/11 challenges, underscores the need for a significant overhaul in how government agencies approach procurement.

In envisioning a future where procurement facilitates rather than hinders technological progress, we can draw inspiration from thought leaders like federal CIO Clare Martorana. Martorana advocates for a transformative approach where government agencies don’t just engage in transactions with vendors but collaborate to develop solutions. Instead of each agency establishing its own digital services agreements, there’s a centralized repository of best-in-class contracting vehicles. This approach would streamline the procurement process, allowing agencies to access the most effective solutions readily.

By consolidating authority, embracing flexibility in contract structures, and fostering a culture that recognizes the potential value in failure, government entities can revolutionize their approach to IT projects.